|

Serpentines and Matchlocks

The

makers of early hand-guns, having furnished a means of holding

the weapon by fitting wooden stocks, were still faced with

the problem of ignition. Using a red-hot iron or wire, or

burning tinder, to set off the priming powder made it necessary

to have a fire or brazier near at hand. The

makers of early hand-guns, having furnished a means of holding

the weapon by fitting wooden stocks, were still faced with

the problem of ignition. Using a red-hot iron or wire, or

burning tinder, to set off the priming powder made it necessary

to have a fire or brazier near at hand.

Shown here is a musketeer, early 17th

century. The musket of the period was an unwieldy weapon,

weighing some 20lb. It was fired from a rest consisting

of a wooden rod topped with a metal fork. Also shown is

the matchlock system of ignition.

Late in the 14th century came a solution

to this difficulty, with the invention of the slow match.

Saltpetre (potassium nitrate), one of the ingredients of

gunpowder, was dissolved in water. Lengths of tow, were

soaked in the solution and allowed to dry, would smoulder

slowly when lit. This match gave the gunner greater freedom

movement.

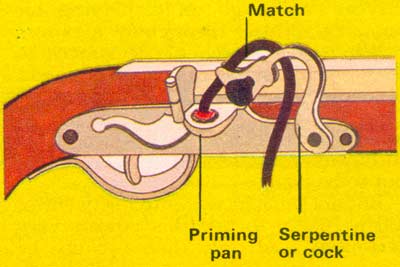

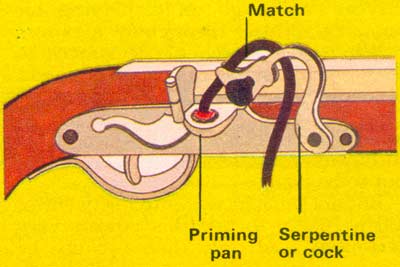

It remained a difficult task, however,

to apply this match to the touch-hole in the heat of battle;

and more effective marksmanship would obviously be possible

with two hands free to manipulate the gun. So a system of

ignition was devised with an S-shaped piece metal, called

the "serpentine" or "cock", attached

to the side of the gun. The match was held in its upper

end, and the serpentine pivoted to lower the match into

the priming pan.

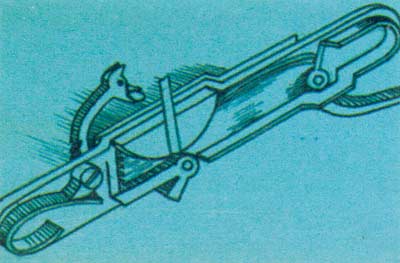

This system soon developed into the

matchlock mechanism. In this the cock was held clear of

the priming pan by a spring. To fire the gun, the spring

was released by means of a trigger action

The Wheel-Lock

We have seen the advantage gained by

replacing the old hand ignition system for guns by the matchlock.

But gun-makers were always on the look-out for improvements.

The fact that flint and other minerals could be used to

produce sparks had been known from early times. It was this

knowledge which led to the introduction, about the end of

the 15th century, of what is called the wheel-lock.

A sketch of a wheel-lock mechanism

is included in the Codex Atlanticus of Leonardo da Vinci,

the Italian artist, scientist and inventor of that period.

It is not known, however, whether it was his own design,

or copied from an existing wheel-lock.

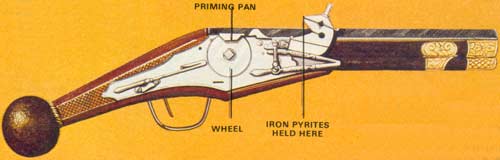

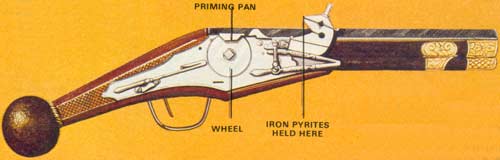

The

wheel-lock works very much like a modern flint lighter.

The priming pan is on the side of the gun and a toothed

wheel is situated below, with its top edge protruding through

a slot into the pan. The wheel is rotated by a spring, which

is wound up with a key. In front of the pan is the cock,

or "dog-head", holding a piece of iron pyrites. The

wheel-lock works very much like a modern flint lighter.

The priming pan is on the side of the gun and a toothed

wheel is situated below, with its top edge protruding through

a slot into the pan. The wheel is rotated by a spring, which

is wound up with a key. In front of the pan is the cock,

or "dog-head", holding a piece of iron pyrites.

When the trigger is pressed, the wheel-spring

is released and the cock pivoted down to bring the pyrites

into contact with the teeth of the rotating wheel. The resultant

sparks ignite the powder in the pan.

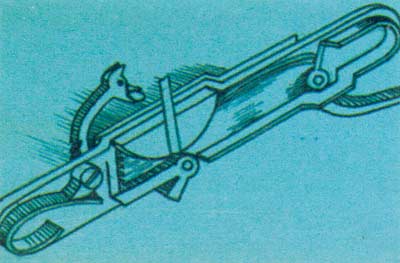

Though the principle is simple, the

mechanism is in fact very intricate, and may have as many

as 50 components. The main advantage of the wheel-lock was

that it enabled the user to have his weapon ready for firing

at any time. This had not been possible with the matchlock,

since the match would smoulder for an indefinite period.

The danger of accidental discharge was also reduced.

Roman Candle Guns

Having invented the wheel-lock, the

gun-maker next turned his hand to designing guns that could

fire two or more rounds without reloading.

The

obvious answer to this need was to make guns with two or

more barrels, and a lock for each barrel. Many weapons were

designed on these lines, including the German 16th century

gun illustrated here. It has two barrels one above the other;

each barrel has its own wheel-lock. The

obvious answer to this need was to make guns with two or

more barrels, and a lock for each barrel. Many weapons were

designed on these lines, including the German 16th century

gun illustrated here. It has two barrels one above the other;

each barrel has its own wheel-lock.

In another system two or more charges

of powder and ball were loaded in a single barrel, separated

by wads. These were fired in turn, starting from the front

or muzzle end, through a succession of touch-holes, each

ignited by a separate lock.

A development of this was the Roman

Candle gun. The bullets used in this had holes drilled through

them, filled with powder. It was only necessary to fire

the front charge to set going a powder-train through the

barrel.

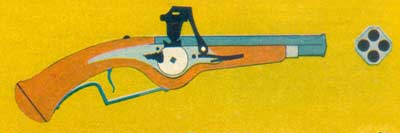

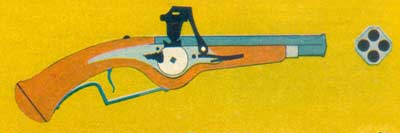

A more complicated form of Roman Candle

gun is the 17th century pistol shown. It has four barrels.

The first is loaded with one round of powder and shot in

the normal way; the second with powder only; the third and

fourth with a number of bullet and powder charges. When

the first barrel is discharged by means of its wheel-lock,

it ignites the powder in the second through a touch-hole

towards the muzzle. The second barrel is linked alternately

to the third and fourth barrels by a row of touch holes.

As its powder burns backwards, it sets off these charges

one by one. With all such weapons, the discharge, once started,

cannot be stopped.

The Snaphaunce

About the time when the wheel-lock

was coming into general use, or certainly not long afterwards,

yet another form of ignition for guns was introduced. Instead

of iron pyrites subjected to friction against a revolving

steel wheel, it used flint struck against steel to produce

a spark.

These

guns may be called the first of the flintlocks; but for

convenience of classification they are nowadays generally

termed "snaphaunce" guns, to distinguish them

from the more sophisticated forms of flintlock introduced

in the 17th century. These

guns may be called the first of the flintlocks; but for

convenience of classification they are nowadays generally

termed "snaphaunce" guns, to distinguish them

from the more sophisticated forms of flintlock introduced

in the 17th century.

The snaphaunce gets its name from the

Flemish schnapp-hahn, "pecking cock". This refers

to the action of the cock which holds the flint. Unlike

the dog-head in most wheel-lock weapons, the cock was situated

behind the priming pan (also called the flash-pan). In other

respects its action was similar. The steel (known as the

"battery") was on an arm pivoting over the priming

pan from the front.

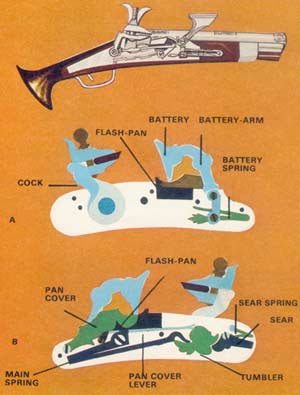

Pressure on the trigger resulted in

the following movements: (1) A lever action opened the sliding

cover of the flash-pan. (2) The battery pivoted backward

over the pan. (3) The cock pivoted forward so that the flint

struck the battery and produced the spark.

The battery-arm bore on an exterior

spring in such a way that it could be retained in the "safe"

position, forward of the pan, if required. The cock could

not then cause a spark if accidentally released.

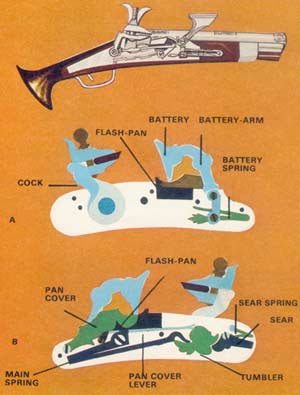

Our illustration shows a fine example

of the snaphaunce. It is a late 16th century German pistol.

The diagrams show (A) the exterior and (B) the interior

mechanism of a typical snaphaunce.

The Cap

One of the drawbacks of early methods

of firing a gun was the "hangfire". This was the

delay between igniting the priming and the firing of the

main charge. To obtain instantaneous discharge it was necessary

to find a faster means of ignition.

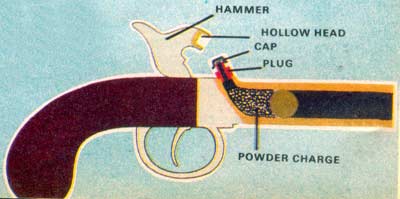

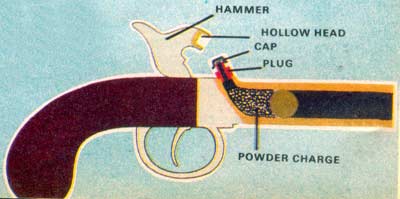

At the beginning of the 19th century,

a Scottish clergyman named Alexander Forsyth produced a

solution to the problem. It was known that the chemical

compounds called fulminates would explode when struck. Forsyth

devised a method of using fulminate of mercury for firing

a gun. His lock had a hammer instead of the cock of the

flintlock. A hollow plug was screwed into the touch-hole.

Pivoting on the side of the gun was a magazine, shaped like

a scent-bottle, containing the detonating powder.

When the "scent-bottle" was

turned it dropped a small quantity of the fulminate into

the plug. The trigger released the hammer, which drove a

firing-pin into fulminate.

Various

improvements followed, but the one which gained general

acceptance was the percussion cap, illustrated here. It

was generally made of copper, and shaped like a hat, with

the fulminate in the "crown". The cap was placed

over an iron nipple which was screwed into the breach of

the gun. When the hammer fell, it crushed the cap against

the top of the nipple, exploding the fulminate and firing

the powder through the hole in the nipple. The hammer was

hollowed out so that it entirely enclosed the percussion

cap. As in the pocket pistol illustrated, hammers were later

mounted centrally on top of the gun, instead of at the side.

- Article lifted from an old series of magazines published between 1970 and 1975 by IPC Magazines, called 'World of Wonder'.

|

The

makers of early hand-guns, having furnished a means of holding

the weapon by fitting wooden stocks, were still faced with

the problem of ignition. Using a red-hot iron or wire, or

burning tinder, to set off the priming powder made it necessary

to have a fire or brazier near at hand.

The

makers of early hand-guns, having furnished a means of holding

the weapon by fitting wooden stocks, were still faced with

the problem of ignition. Using a red-hot iron or wire, or

burning tinder, to set off the priming powder made it necessary

to have a fire or brazier near at hand.

The

wheel-lock works very much like a modern flint lighter.

The priming pan is on the side of the gun and a toothed

wheel is situated below, with its top edge protruding through

a slot into the pan. The wheel is rotated by a spring, which

is wound up with a key. In front of the pan is the cock,

or "dog-head", holding a piece of iron pyrites.

The

wheel-lock works very much like a modern flint lighter.

The priming pan is on the side of the gun and a toothed

wheel is situated below, with its top edge protruding through

a slot into the pan. The wheel is rotated by a spring, which

is wound up with a key. In front of the pan is the cock,

or "dog-head", holding a piece of iron pyrites.

The

obvious answer to this need was to make guns with two or

more barrels, and a lock for each barrel. Many weapons were

designed on these lines, including the German 16th century

gun illustrated here. It has two barrels one above the other;

each barrel has its own wheel-lock.

The

obvious answer to this need was to make guns with two or

more barrels, and a lock for each barrel. Many weapons were

designed on these lines, including the German 16th century

gun illustrated here. It has two barrels one above the other;

each barrel has its own wheel-lock.

These

guns may be called the first of the flintlocks; but for

convenience of classification they are nowadays generally

termed "snaphaunce" guns, to distinguish them

from the more sophisticated forms of flintlock introduced

in the 17th century.

These

guns may be called the first of the flintlocks; but for

convenience of classification they are nowadays generally

termed "snaphaunce" guns, to distinguish them

from the more sophisticated forms of flintlock introduced

in the 17th century.