|

By Larry Irons

Introduction

Many wargame rulesets are designed

for the period of the smoothbore musket, for example, English

Civil War, Seven Years' War, and the Napoleonic Wars. However,

most of these rules do not include information on how the

casualty system was devised. This article analyzes the factors

related to the smoothbore musket that should be addressed

in wargame rules and simulations for this period.

Early Smoothbore Musket

The smoothbore musket was a long-ranged

firearm derived from the earlier arquebus (or hackbutt)

during the 16th century. The musket was initially heavier

than the arquebus, requiring a wooden rest to aim, and had

a length of 6 ft compared to the arquebus's 4 ft. Calibers

of the weapons varied from 0.50 inch to 0.75 inch. The musket

also had a longer range and higher muzzle velocity than

the arquebus. The arquebus was preferred by some, because

of its easier handling (skirmishers preferred the arquebus)

and faster rate of reload (2 or more minutes for the musket

versus 1 to 2 minutes for the arquebus). The heavier musket

also absorbed more of the recoil at discharge. However,

the lower muzzle velocity of the arquebus did not always

penetrate armor, which was still worn by pikemen and cavalry.

In the Spanish and Imperialist armies, there were bodies

of both arquebusiers and musketeers.

The

bayonet was not invented yet. Arquebusiers and musketeers

depended on bodies of pikemen to defend themselves from

cavalry charges. The musketeers and arquebusiers also carried

swords for fighting hand-to-hand. However, their firearms

were usually used as clubs in melees. The

bayonet was not invented yet. Arquebusiers and musketeers

depended on bodies of pikemen to defend themselves from

cavalry charges. The musketeers and arquebusiers also carried

swords for fighting hand-to-hand. However, their firearms

were usually used as clubs in melees.

Both weapons used a matchlock to fire

the weapon and were muzzle loaded. To load the weapon, the

shooter would unplug a wooden container called an apostle

(because there were 12 of them) from his leather bandoleer.

He would then pour a pre-measured amount of loose gunpowder

from the apostle into the muzzle of the barrel. Then a lead

ball from a sack was placed into the muzzle and rammed home

into the chamber with a wooden scouring stick (a.k.a. ramrod).

The powder pan on the side of the musket barrel was opened

and loose gunpowder from a powder flask was poured into

it. A glowing match made from cord soaked in saltpeter was

placed in the hammer of the lock. The shooter would aim

his weapon. The trigger was pulled forcing the match into

the pan igniting the powder. The flash from the pan would

travel into the chamber through a hole and ignite the powder.

The expansion of gases would force the ball on its way to

the intended target.

The powder in the chamber ignited slowly.

Too much powder resulted in the ball leaving the muzzle

before all of the powder had been ignited. A correct balance

between charge size and length of barrel was important to

ensure that all of the powder was ignited before the ball

left the muzzle of the barrel. The correct relationship

between charge size and barrel length maximizes the muzzle

velocity of the ball. In general a higher muzzle velocity

results in greater range and accuracy, and better penetration

into armor.

Reloading took a long time, involving

some 48 distinct movements. Elaborate methods were designed

to provide a continuous stream of fire. Troops were deployed

in formations of 6 or more ranks to deliver their shots

one rank at a time. After one rank of shooters fired a newly

reloaded rank would move in front of the them (fire by introduction)

or the recent shooters would move to the rear and reload

(fire by extroduction), exposing a loaded rank.

During the late 16th and early 17th

centuries many Protestant armies experimented with lighter

muskets that were easier to handle and load. This decreased

the reload times down to 2 or less minutes. In some cases

the musketeer did not need a musket rest. The arquebus was

dropped in favor of the lighter muskets. The lighter muskets

still had good armor penetration power. This and the increasing

effectiveness of light artillery caused armor usage to diminish.

The Protestant armies, armed with their

lighter muskets, experimented with salvo fire. This involved

the fire of two or more ranks simultaneously. The Huguenots

of France under Henry of Navarre first used this method

during the French Religious Wars. The Dutch in their war

of independence also used this method against the Spanish.

Finally the Swedes under Gustavus Adolphus used salvo fire

very effectively. A Swedes brigade is reported to have stopped

seven Imperialist cavalry charges with salvo fire at the

Battle of Breitenfeld (1631) during the Thirty Years' War.

Another major contribution by the Swedes

was the adoption of the paper cartridge. A musketeer was

equipped with a cartridge box that contained pre-made rounds

of powder and ball. The musketeer would grab a cartridge

from the box, then bite down on the ball and tear the cartridge

open. He would pinch off a small amount of powder in the

cartridge and pour the remainder into the muzzle of his

musket. The remaining powder was placed into the pan. The

ball was retrieved from his teeth and placed into the muzzle.

Then he rammed the ball down the barrel until it was well

seated into the chamber. The musketeer then fired his weapon

as before. The Swedish combination of lighter, handier muskets,

with paper cartridges, and salvo tactics enabled the Swedes

to reload at one-minute intervals.

Flintlocks

In the late 16th century, the firelock

was invented. This invention eliminated the glowing match

and replaced the match mechanism with a flint. The flint

struck against steel over the pan, emitting sparks. The

flintlock decreased the reload time, but was more expensive

than the matchlock mechanism. The abundance of gunpowder

in the artillery train prohibited the use of burning objects

(glowing match) in the vicinity and the firelock became

the preferred weapon for the artillery train guards. The

firelock was also known as a fusil, and this is the origin

of the term fusilier. Flintlocks became more popular over

time as the cost diminished and reliability improved. During

the Malburian wars of the early 18th century, the matchlock

was completely replaced by the flintlock. Another advantage

of flintlocks over firelocks is formation. Matchlocks require

more distance between individuals because of the glowing

match and the necessity of moving ranks after each salvo,

whereas the flintlock allows a close ordered formation.

Volley Fire

In the late 17th century, the English

and Dutch armies adopted volley fire, coinciding with the

adoption of the flintlock musket. Volley fire differed from

salvo fire. Salvo fire involved the simultaneous fire of

entire ranks of the battalion. Volley fire involved the

simultaneous discharge of all men in one sub-unit, called

a platoon, which was deployed in three ranks. The entire

battalion would be divided into 8 or more platoons. Each

nation adopted different firing orders of the platoon. One

popular method involved the platoons alternating their fire,

first from the outside, right then left, and continuing

the firing order toward the center of the battalion. This

allowed a continuous fire to be presented to the enemy and

minimized the obscurity of the target caused by smoke. Also

there was no need to exchange ranks as in salvo fire. Therefore

there was less confusion after discharging the musket prior

to reloading.

All European nations adopted the volley

fire method by the end of the Malburian Wars in the early

18th century. The Prussians made modifications to the method

to allow troops to reload while marching during the War

of the Austrian Succession. However, this decreased the

accuracy enough that such volleys were ineffectual. The

British perfected volley fire to a science during the Napoleonic

Wars. A well-trained musketeer of the British army during

the early 19th century could reload in 30 seconds or less.

Misfires and Fouling

Misfires happened due to a number of

circumstances. The method of loading the musket introduced

inaccuracies in the amount of powder used, causing variations

in the performance of the weapon. The firing mechanism,

with its crude method of priming, was also by no means reliable

and misfires occurred frequently. Laurema (1956) states

that at the end of the eighteenth century 15 percent of

musket shots misfired even in dry conditions. The incidence

of misfires must have been appreciably higher in the wet

conditions which so many battles were fought in Western

Europe. It would therefore seem likely that nearly a quarter

of the musket shots misfired.

Gunpowder leaves a residue after igniting

inside the chamber of a musket. This residue continues to

accumulate during the heat of battle. This increases the

reload time and increases the chance for a misfire. Also

flints are brittle and can break, requiring replacement.

During a battle a battalion will tend to increase its reload

time and deliver less shot as the fouling increases over

time. Therefore the most effective volley will be the initial

volley and the early subsequent volleys. Some wargame rules

give a bonus for the first time a unit shoots. Depending

on the time scale of the ruleset, this is a valid factor.

Bayonets

Although the bayonet is not a firearm,

after its general introduction, it becomes an integral part

of the smoothbore musket. In the 16th and 17th centuries,

musketeers sometimes adopted defensive weapons to protect

themselves from cavalry. The most portable weapon was the

Swedish feather (a.k.a. swine feather). The Swedish feather

was a pointed stake and musket rest combination. The stake

was planted pointing toward the enemy to act as a defensive

obstacle. Gustavus Adolphus's Swedish army used Swedish

feathers against the Polish Army, which had a high percentage

of cavalry. During the Thirty Years' War, the Swedes did

not use Swedish feathers to any great degree, probably because

the terrain offered better cover against cavalry and there

was less cavalry in Germany than Poland.

In the latter half of the 17th century,

French musketeers started to use plug bayonets. The bayonet

literally plugged into the muzzle of the musket. This had

the unfortunate side effect of no longer allowing the musket

to be neither reloaded nor fired. Later still the ring bayonet

was invented. This was a bayonet with a ring to allow it

to be attached to the barrel. This allowed the musket to

be reloaded and fired while the bayonet was attached. However,

during melees the ring bayonet was known to sometimes fall

loose.

Finally the socket bayonet was invented

in the late 17th century. This allowed a bayonet to be securely

attached to the barrel of the musket. This also eliminated

the need for pikemen to support the musketeers. The last

pikemen disappeared from the rolls of the regiments in the

early 18th century.

Iron Ramrods

The next major invention for the smoothbore

musket was the iron ramrod. Prior to the mid-18th century,

ramrods were made of wood. A musketeer had to be careful

in the heat of battle not to push too hard with his ramrod

or risk breakage. The windage had to be increased to allow

the ball to be seated home. This decreased the accuracy

of the musket using the wooden ramrod. Frederick the Great

prior to the War of the Austrian Succession (1744-1748)

implemented the iron ramrod. This invention helped Frederick's

Prussians to increase their overall reload speed as well

as accuracy. Other European nations adopted the iron ramrod

after the War of the Austrian Succession.

Accuracy

The smoothbore musket is not a very

accurate weapon by today's standards. It was said that an

individual, aiming at a target the size of a man at a range

of 150 yards, had as much chance of hitting the target as

he did of hitting the moon. However, from the earliest use

of the musket target formations were in close order. The

still medieval-like bodies of troops deployed on the battlefield

to enhance melee effectiveness. The fighting of melees was

still the major method of winning battles. Infantry had

to deploy in dense and deep formations to prevent from being

run down by the heavily armored cavalry. Musketeers had

to stay close to the pikemen for defense against the cavalry.

Therefore deploying an army in close order formations was

a necessity.

The inaccuracy of the musket was less

of a disadvantage, because aiming at a formed body of troops

had a reasonable good chance of hitting somebody. It is

also easier to control a body of troops in formation than

it is in open order, therefore a formed group of musketeers

could deliver more shots in a given period of time than

an unformed body. During the period from the late 16th century

to the early 19th century, the primary method to deliver

fast and effective fire was dictated by keeping the musketeers

formed.

The accuracy of the weapon is partly

dictated by the windage, the difference between the interior

barrel diameter and the ball's diameter. The windage also

affects the speed of reloading and the muzzle velocity.

The greater the windage, the easier it is to ram home the

ball into the barrel. This also allows more gas to escape

from the barrel without pushing the ball out of the barrel.

Therefore less windage will yield a higher muzzle velocity

and higher accuracy. The tactics of the time influenced

the armies to have more windage to increase the reload speed.

More volleys meant more casualties. Accuracy was not a factor.

The use of skirmishers during the period

of the smoothbore musket to harass the enemy was not uncommon.

Typically the skirmishers used the same weapon as the formed

troops. Though shots at longer distances were inaccurate,

an aimed shot at 50 yards could hit an intended, individual

target.

Trials

Despite the inaccuracies of the smoothbore

musket, studies were made by various nations in the 18th

and 19th centuries to determine the effectiveness of a body

of musketeers against the enemy. At the trials a group of

musketeers would aim and shoot at a target the size of a

battalion or company and count the number of hits at one

or more known ranges. Also there were trials to determine

how many volleys could be delivered over a given length

of time. Prussian trials in 1810 found that a musketeer

could deliver 2 to 2-1/2 rounds per minute, which is comparable

to the British rate of fire. However, the Prussian trials

also showed that there was a lot of variability in the reloading

rate.

Hanoverian experiments in 1790 showed

that when fired at various ranges against a representative

target (a placard 6 ft high and up to 50 yd long for infantry,

8 ft 6 in high for cavalry) the following results were achieved

at the ranges show:

Percentage of musket ball hits on a

fixed target

| |

Target Type |

| Range (yd.) |

Infantry |

Cavalry |

| 100 |

75.0% |

83.3% |

| 200 |

37.5% |

50.0% |

| 300 |

33.3% |

37.5% |

The weapon used was an infantry musket

firing a 3/4-oz ball and the shooters were able to aim each

shot. Obviously the cavalry target received more hits because

it was a bigger target.

Another experiment described by Mueller

(1811) involved the use of aiming versus no aiming. Infantrymen

in the aiming group were encouraged to aim their muskets

as hunters would instead of just pointing it roughly ahead

and pulling the trigger. Each group fired 1,000 rounds against

a cavalry target. The results of this experiment are shown

below:

| Range (yd.) |

Aimed shots |

Unaimed shots |

| 100 |

53.4% |

40.3% |

| 200 |

31.8% |

18.3% |

| 300 |

23.4% |

14.9% |

| 400 |

13.0% |

6.5% |

These results demonstrate that

aimed fire is significantly better than unaimed fire, even

for a smoothbore musket, especially more significant at

longer ranges. This indicates that skirmishers using aimed

fire from long range can actually cause significant casualties.

However, skirmishers also tend to shoot less often than

formed volley shooters, roughly canceling out the increased

benefit of aiming. British infantry of the Napoleonic Wars

were taught to aim their volleys. Aimed fire and the excellent

British reload training would explain the factors contributing

to the renowned British, superior fire discipline.

It must be emphasized that these trial

results are for laboratory-like conditions. There was no

stress upon the shooters as would be expected on the battlefield.

Also the targets are solid placards. Infantry and cavalry

are composed of individuals with gaps between them. Therefore,

actual battlefield effectiveness would be much less than

the above results.

However, one can make an inference

from these data on accuracy versus range to target. It appears

that the accuracy is inversely proportional to the distance.

In other words, the accuracy at range R is double that of

range 2R, or double the range and cause 1/2 as many casualties.

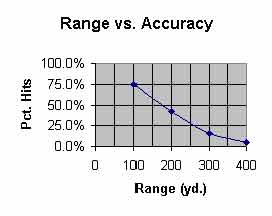

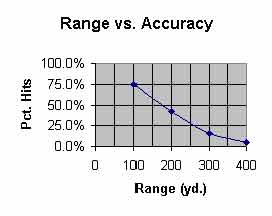

Greener (1881) gives the following figures for a percussion

musket, which was only marginally better than the flintlock

as regards range and accuracy, as follows:

| Range (yd.) |

Percentage of hits |

| 100 |

75% |

| 200 |

42% |

| 300 |

16% |

| 400 |

4.5% |

These results were against a target,

which was 6 ft high by 20 ft long.

Actual Battlefield Results

At the Battle of Blenheim (1704)

the British with five battalions attacked the French fortified

positions along a front of 750 yds. The French had approximately

4,000 fusiliers deployed along 900 yds. The French opened

fire at 30 yards with a single devastating volley causing

33 percent casualties to the British attacking force. This

came to approximately 800 casualties. Therefore 20 percent

of the French rounds were effective. If we assume that 15

percent of the French muskets misfired, this gives an effective

rate of 23 to 24 percent of those muskets that actually

fired.

At the Battle of Fontenoy (1745)

five British battalions with a total strength of 2,500 men,

less a few hundred men due to French artillery fire, let

loose a volley at 30 yards against an attacking force of

five French battalions. The British volley caused 600 casualties

to the French. This would mean that the British muskets

were hitting with an effective rate of 25 percent.

At the Battle of Minden (1759) Hughes

estimates that the effectiveness of musketry by both British

and French was less than two percent per volley. In this

battle the French and British engaged at much longer ranges,

100 to 150 yards. At the Battle of Albuera (1811) a French

divisional column attacked the British position. The British

muskets averaged a two-percent effectiveness rating at that

battle at a range of 100 to 150 yards. However, at the same

battle on the French left flank, the average effectiveness

was about 5-1/2 percent per volley for both sides. Hughes

concluded that at Albuera the actual effectiveness dropped

off rapidly with range between 30 and 200 yards. He also

stated that smoke on the battlefield often obscured the

aim of the shooters, which would lower the effectiveness

dramatically. Hughes also concluded that the infantry of

the first half of the 18th century are better trained than

those of the later 18th and early 19th centuries. If true,

then one would expect higher musket effectiveness for the

earlier period.

Based on the above historical incidences,

wargame rules should take incorporate a range attenuation

factor. Range attenuation simulates the effectiveness of

the smoothbore musket in battle. The first volley bonus

has already been discussed. However, the effectiveness of

infantry musketry is also affected by training, discipline,

morale, and local conditions (smoke, cover, etc.).

Range of Engagement

Bodies of musketeers generally engaged

in firefights at ranges of 100 yards. However, in the early

period, it was not unusual to engage at longer ranges. During

the 18th century, it was not unusual to fire an initial

volley at ranges of less than 50 yards. Firefights between

opposing lines of infantry tended to last no more than 15

minutes. At the end of this time one side or the other would

give way due to morale loss. Wargame rules that use a first

volley bonus cause a tendency amongst the players to withhold

their fire until within the most effective range. This tends

to simulate actual tactics of the period.

Clauswitz

Clauswitz was a general in the Prussian

army during the Napoleonic Wars. After those wars he wrote

a famous treatise on warfare, "Clauswitz on War."

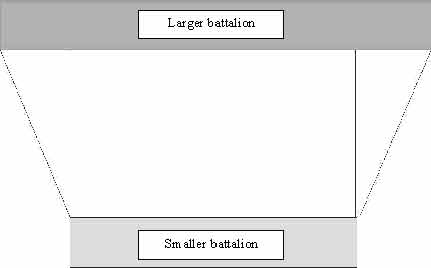

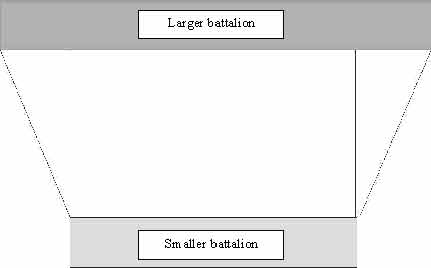

One of his observations was that a body of troops can engage

an enemy of frontage up to 50% of its own. Both sides would

suffer the same casualty rate. His reasoning was that the

smaller frontage unit would present less of a target area.

The larger unit would present a greater target area, allowing

more hits by the smaller unit. His premise was that one

should deploy less troops on the line and hold back the

rest in reserve. I have never seen a set of rules (other

than my own) that takes into account the frontage of the

target in the casualty calculations.

Most battalions engaged in firefight

at a range of 100 yards. A battalion's front was about 200

yards. Based on these one can infer the approximate scatter

angle for a smoothbore musket is about 22-1/2 degrees. Another

corollary for wargame rules is that a unit firing at a larger

target gets a "to hit" bonus that is roughly equal

to 50% for a target(s) covered within its full arc of fire.

Illustration of Clauswitz's observation

Further Improvements

After the Napoleonic Wars, the next

major innovation for the smoothbore musket was the invention

of the percussion cap. The percussion cap eliminated the

use of the flint. This invention further reduced misfires

due to the flint failing. It also improved reliability in

high winds, because there was no need for a firing pan with

loose powder. It also decreased the reload time. Percussion

muskets were also known as caplocks.

The caplock smoothbore musket was the

ultimate weapon before the invention of the rifled musket.

The invention of the greased patch and the rifling of the

musket barrel in the 1850s ended the span of four centuries

of the domination of the smoothbore musket in warfare.

Conclusions

The smoothbore musket was a firearm

that dominated the battlefield from the 16th until 19th

centuries. Wargame rules writers should look carefully at

historical data to account for certain factors that influenced

tactics on the battlefield. There is certainly hard evidence

to give British Napoleonic infantry bonuses for their fire

discipline due to greater rate of fire and aimed shooting.

There is also evidence both from observation and mathematical

analysis to support a bonus for shooting at a larger frontage

target. Depending on the time scale of the ruleset, a bonus

for the initial volley is appropriate. The first volley

bonus tends to cause players to withhold the fire of their

battalions until within effective range. However, the general

effectiveness of musket fire is about 3 to 5 percent at

ranges of 100 to 200 yards, which is far less than the theoretical

maximum.

Bibliography

- Duffy, Christopher, 1974, The Army

of Frederick the Great, Hippocrene Books, Inc.

- Duffy, Christopher, 1977, The Army

of Maria Theresa, Hippocrene Books, Inc.

- Duffy, Christopher, 1981, Russia's

Military Way to the West, Routledge & Kegan Paul

- Dupuy, R. Ernest, and Dupuy, Trevor

N., 1977, The Encyclopedia of Military History

- Greener, W. W., 1881, The gun and

its developments

- Gush, George, 1975, Renaissance

Armies, Patrick Stephens, Ltd.

- Gush, George, and Windrow, Martin,

1978, The English Civil War, Patrick Stephens, Ltd.

- Haythornwaite, Philip, 1983, The

English Civil War 1642-1651, Blandford Press

- Held, Robert, 1970, The Age of

Firearms, Gun Digest Company

- Hughes, Major-General B. P., 1974,

Firepower, Arms and Armour Press

- Laurema, Matti, 1956, L'artillerie

de campagne franH ais pendant les guerres de la revolution

- Mueller, William, 1811, Elements

of the Science of War

- Nosworthy, Brent, 1990, The Anatomy

of Victory, Hippocrene Books

- Parker, Geoffrey and Angela, 1977,

European Soldiers, Cambridge University Press

- Von Pivka, Otto, 1979, Armies of

the Napoleonic Era, Taplinger Publishing Company

- Von Reisswitz, B., 1824, Kriegspiel,

Netherwood Dalton & Co., Ltd.

- Wagner, Eduard, 1979, European Weapons

and Warfare 1618-1648, Octopus Books Limited

|

The

bayonet was not invented yet. Arquebusiers and musketeers

depended on bodies of pikemen to defend themselves from

cavalry charges. The musketeers and arquebusiers also carried

swords for fighting hand-to-hand. However, their firearms

were usually used as clubs in melees.

The

bayonet was not invented yet. Arquebusiers and musketeers

depended on bodies of pikemen to defend themselves from

cavalry charges. The musketeers and arquebusiers also carried

swords for fighting hand-to-hand. However, their firearms

were usually used as clubs in melees.